Mental Health In The Workplace

Caterina Violi

1. Introduction

In this White Paper, we will explore the multifaceted nature of mental health in the workplace, examining its prevalence, underlying stressors, and the imperative for businesses to address it proactively. We will highlight the pivotal role of company culture in fostering a supportive environment where employees can thrive, free from stigma and barriers to seeking help.

Moreover, we will argue that leadership is crucial in shaping organisational attitudes and behaviours surrounding mental health. By setting the tone, promoting open dialogue, and championing mental wellbeing initiatives, leaders can profoundly influence the workplace culture and enhance employee resilience and engagement.

By embracing a comprehensive approach that encompasses cultural transformation, leadership commitment, and alignment with evolving workforce values, businesses can mitigate the costs of untreated mental health issues and cultivate a resilient, thriving workforce.

1.1. Mental Health Isn’t Something New: We Just Define It Better Now

Recently, the World Health Organisation (WHO) updated their definitions to include mental health, stating: “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” so mental health is more than just the absence of mental disorders or disabilities.

Such a holistic definition is centred around two main ideas: there is no health without mental health, and health is not just the absence of illness (Kelly C. et al., 2015).

The WHO also conceptualises Mental Health as a state of wellbeing where the individual realises personal abilities, is able to cope with life’s stressors, can be productive, and contributes to the community.

Across all business types, charitable organisations, and the public sector, leaders today are are familiar with terms such as ‘wellbeing at work’ and ‘mental health awareness’, but despite an appetite to make meaningful changes, many struggle to implement effective solutions; this goes deeper than aiming for the traditional ‘good work-life balance’ and society’s empathy towards mental health is evolving with fresh scientific knowledge and updated experience of the human condition.

1.2. Mental Health Isn’t Something New: We’ve Evolved Our Approach

Our understanding of mental health in the workplace is evolving, and moving away from Victorian-era legacy attitudes. For example, there’s now a strong business case for modern workforces to adopt ‘mental health first aiders’ which help organisations to react appropriately – and quickly – to provide internal support for their employees.

Employing mental health first aiders benefits the organisation and the people behind it. They protect human welfare by making the help more obvious and accessible; proactively identifying early signs that someone might need help; and working with individuals before their issues turn into absence. They improve productivity with less and/or shorter operational interruptions; staff retention is improved through higher morale and fostering positive supportive cultures. By protecting its people, an organisation protects their bottom line too. (We explore this further in 6.2 below.)

1.3. Mental Health Isn’t Something New: It Shouldn’t Be A Tick Box

Working with our own clients to create workplaces which are supportive of wellbeing and mental health, we regularly experience leaders who know that they need to be inclusive of the less-forthcoming members of their teams; they know they need to create a safe space for people to have feelings or personal challenges, and to acknowledge these feelings and challenges as being valid.

But sometimes this just equates to having someone in HR you can send people to.

While it isn’t a bad thing – having that ‘someone in HR’ who is willing-and-able to step-up as ‘the person to talk to’ about employees’ mental health and wellbeing – it isn’t a substitute for creating the safe, supportive and inclusive team environment that delivers higher morale, better staff retention, and a productive workforce.

Creating a truly safe and inclusive workplace culture unlocks many benefits; it brings the best out of people, fostering more innovation and creativity, unlocking collective intelligence and cross-departmental collaboration.

What we often notice, is that leaders tackling mental health issues focus on making sure they aren’t creating an unbearable place to work; that they are doing what they can to prevent churn; and showing they have taken steps to ensure that the problems that nobody want to openly talk about, are talked about, somehow, but ideally somewhere else.

Avoidance tactics and tick-box exercises for mental health result in a fearful and ‘brush-it-under-the-carpet’ culture, where fitting in is more important than creating a workplace where people can feel they belong.

Token gestures only make a limited difference, and if leaders are to make a real impact on mental health, and reap the benefits of a healthy and engaged workforce, it is imperative that they understand the problem they are facing and they’re confident in their ability to address it.

That, in turn, may mean asking some difficult questions.

“If you want to improve the organisation, you have to improve yourself

and the organisation gets pulled up with you.”

– Indra Nooyi, CEO, PepsiCo

2. Mental Health In The Workplace

In the context of the workplace, where individual contribution and productivity are paramount, the WHO definition assumes considerable importance. Moreover, the significance of mental health issues in the workplace becomes even more evident when we look at their prevalence. Unlike occupational hazards, which have historically affected only a fraction of the population (e.g. asbestos), the stressors underlying mental health challenges in contemporary workplaces have the potential to impact the entire workforce (La Montagne et al., 2014).

The most common disorders include depression, anxiety and simple phobia disorders. In addition to clinical disorders, subclinical mental health problems and generalised distress are also prevalent in the working population (Sanders, 2006).

Looking at prevalence data, it is clear that the global scale of the phenomenon today is considerable, and mental health in the workplace today is far from being a niche problem.

Epidemiological data from OECD countries suggests that 1 in every 5 working adults have mental health disorders and substance abuse problems, ranging from moderate (affecting 15% of working adults) to severe (affecting 5% of working adults) (OECD, 2012).

More recent estimates by the WHO suggest that 300 million people are affected by common mental health disorders, and of these 70% are employed (WHO, 2017).

The impact of work on stress levels, in particular, has been studied empirically. In 2017 The American Psychological Association, for instance, found that work was a leading cause of stress amongst US adults.

A birth cohort study conducted in New Zealand went as far as estimating that, at age 32, 45% of incident cases of depression and anxiety in previously healthy young workers were attributable to job stress (Melchior et al. 2007).

3. Mental Health Stressors In The Workplace

The factors behind poor mental health in the workplace are diverse and extensively documented. In some instances they intersect with external circumstances such as work-family conflict and economic insecurity (McKinsey, 2020). In other cases, they are internal and can be related to an imbalance between effort and reward or a lack of career prospects within the business.

In particular, high job strain, a combination of long hours & high demands on the job and a low level of latitude & control over how the job is carried out, is widely recognised as a key stressor in the workplace and one which has been proven harmful to both physical and mental health, including cardiovascular diseases and common mental health disorders (Karasek et al., 1988).

Company culture also plays a pivotal role when it comes to mental health and wellbeing. A toxic culture – where disrespect for employees, lack of inclusivity, cutthroat attitudes, poor interpersonal relationships and abusive behaviours prevail – is a fertile ground for chronic stress and, consequently, low levels of mental health. As highlighted in our White Paper on The Cost of a Toxic Workplace Culture, employees working in these settings suffer greater stress, anxiety, depression and burnout; they also see their risk of suffering a major illness increase between 35% and 55% (Goh, Pfeffer & Zenios, 2016). The impact of a toxic workplace culture also disproportionately affects employees’ from diverse backgrounds who are, generally, more likely to feel a lack of psychological safety stemming from more or less overt discrimination.

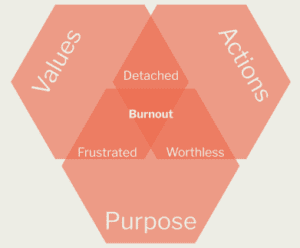

Furthermore, employees’ own values and sense of purpose count. In a recent article, the British Psychological Society reports that research has shown that workers in certain sectors are prone to burnout – a complex, debilitating disorder resulting from chronic exposure to occupational overload, impairing basic cognitive functions such as memory, attention and judgement – when the reality of working on the ground consistently fails to match their values and ideals. In the case of nurses, for instance, the inability to provide safe and compassionate levels of care can generate anxiety.

Similarly, burnout has been found to be associated with a lack of job-congruence in idealistically motivated aid workers, who find themselves overwhelmed and impotent in the face of global challenges (BPS, 2023). Hence, a workplace culture in which employees thrive is not merely a culture which lacks toxicity but one which successfully supports employees’ own values, their sense of purpose, and allows them to thrive within it.

- Further Reading On Workplace Burnout:

📖 Understanding Workplace Burnout

📖 When Stopping Isn’t an Option: Leading your team through burnout

📖 The Illusion of Resilience in Toxic Work Cultures: An Analysis of Burnout

- Free Burnout Training Resource (Watch & Download):

A simple four-step workshop strategy that you can use with your team to bring things back into alignment and build resilience in the face of challenges, and avoid workplace burnout.

🎓 From Burnout to Resilience (Video Explainer & Training Slides)

- One-day Workshop To Overcome The Challenges Of Workplace Burnout:

A workshop that helps you and your team to foster a positive, resilient and collaborative culture, to remove fearfulness, manage and avoid burnout, and achieve inspirational results.

🎓 Navigating with Resilience Workshop

4. Mental Health Trends And Statistics In The Workplace

Mental health disorders amongst adults have been steadily rising in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic not only introduced widespread stress, but has also significantly affected people’s ability to cope with it in the medium to long term, as indicated by emerging data.

A survey of US adults conducted by the American Psychological Association in 2023, for instance, shows that levels of stress three years on from the pandemic have increased across most age groups, with younger working age groups seeing the sharpest rise: increasing from 26% to 34% among 18-34 year-olds; and from 21% to 31% among 35-44 year-olds. By the same token, the likelihood of working age adults in the US having a mental health diagnosis has increased significantly between 2019 and 2023.

Data from Europe shows a similar picture. A recent multi-country study conducted by health and wellbeing provider Telus Health, for instance, found that the likelihood of workers having a diagnosis for depression or anxiety increased in 4 of the 6 countries studied – in Italy, Spain, The Netherlands and Germany – between April ‘23 and October ‘23.

Perhaps even more significantly, in 2019 burnout was officially recognised by the WHO as a health condition, in the wake of a steady tide of cases globally. Although burnout is endemic in some professions centred around the care of vulnerable individuals ( e.g. healthcare, social work), as a phenomenon it is increasingly affecting a wider range of workers and occupations. Recently, the British Psychological Association (BPS) defined the rise in burnout rates as a true epidemic (BPS, 2023).

4.1. Diversity And Mental Health In The Workplace

Mental health in the workplace is not distributed evenly amongst all demographic groups, with notable variations based on ethnicity, gender and economic status.

Recognising the intersection between mental health and diversity in the workplace is crucial, as these factors are closely intertwined.

Individuals from racially diverse and LGBTQ+ backgrounds, for instance, often face a higher risk of experiencing microaggressions, unconscious bias, and lack of recognition for their contributions, as illustrated in our White Paper “Diversity, Equity, And Inclusion For Successful Leadership”. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these stressors can significantly impact these groups’ mental health in the workplace (Smith et al. 2015).

In the US, research indicates that Black-American and Latino/Hispanic-American workers are more likely to experience mental health challenges at work (McKinsey, 2020). A survey conducted by Morning Consulting in 2022 revealed that Latino/Hispanic-American workers exhibit the lowest rates of mental health compared to their Asian-, White-, and Black-American counterparts.

Additionally, while Black-American workers do not report the lowest levels of mental health at work, they are significantly less likely than their white peers to feel a sense of belonging in their working community (50% vs 68%), and to believe that they would receive support from their colleagues if they were struggling mentally (52% vs 63%).

Furthermore, it appears there are marked differences in access to, and usage of, mental health services by ethnic/racial groups, as meta-analysis conducted by Smith et al. (2015) on US data (drawn from more than 130 research studies) highlights.

Two other groups that are disproportionately affected by low mental health levels at work are women and those in lower income brackets (Telus Health, 2014), a pattern that is consistent with broader population data, as highlighted by global estimates by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2017).

- Further Reading on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Workplace:

📖 Enabling Diversity, Equity, And Inclusion For Successful Leadership

4.2. The Importance Of Mental Health And Wellbeing Amongst Young Professionals

The priorities and values of Millenials and young people from Gen Z, in relation to work, mental health and work-life balance, are well documented and diverge significantly from those of older generations.

Recent analysis by Deloitte highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred younger generations to reassess their choices and priorities, placing increasing emphasis on mental health, wellbeing, work-life balance, and purposeful and authentic work in the face of an increasingly disrupted and uncertain world (Deloitte, 2022).

This goes hand in hand with high levels of awareness and likelihood to report suffering from mental health challenges amongst young people. For example, a survey conducted in 2022 by Morning Consult, on behalf of the Marie Christie Institute amongst a sample of young people aged 22-28 in the US, found that just over half (51%) reported needing help for emotional or mental health problems in the past year.

Moreover, younger generations are more likely than their older counterparts to base significant work and life decisions on factors related to mental health.

According to a 2019 survey by Mind Share Partners, 50% of Millennials and 75% of Gen Z respondents had actually left jobs, at least partly, because of mental health.

Similarly, over a third (38%) of young professionals aged 22-28 surveyed by Morning Consult in the US say their workplace negatively impacts employee mental health and wellbeing.

There is also evidence suggesting that younger generations are more vocal than older ones about the need to address mental health issues in the workplace.

The Morning Consult survey findings show that 60% of young professionals think employers should do more in supporting employees in this area.

With young generations’ gradual coming of age, mental health and wellbeing are poised not only to gain prominence amongst the majority of the workforce, but also to become increasingly relevant for future generations of leaders and senior executives within businesses.

5. Why Is Mental Health Important In The Workplace?

If we accept the WHO’s definition that mental health is an integral part of human health, one could argue that supporting employees’ and workers’ wellbeing becomes a moral imperative that every company should be seeking to uphold.

Investing in wellbeing isn’t just the right thing to do, or something only younger generations benefit from – it’s also good for business. Happier and healthier people take less sick days, and they’re more engaged, innovative, productive, and profitable.

Since a significant portion of life is spent at work, creating cultures where mental health is authentically valued and understood, and embedded in everyday practice, is crucial for global human health, and by extension, the future of our global economy.

5.1. The Cost Of Poor Mental Health In The Workplace

Beyond the simple moral imperative, fostering a supportive workplace for mental health carries significant benefits for businesses and the healthcare system alike, particularly in terms of costs:

- Globally, the annual cost of poor mental health in the workplace in 2010 has been estimated to be around:

≈ $2.5 Trillion ($2,500,000,000,000.00) - – less than a third of this (32%) accounts for direct costs of treatment:

≈ $0.8 tn ($800,000,000,000.00) - – the majority (68%) of the $2.5 Trillion is linked to the indirect cost of being physically at work but not working at full productivity, due to a lack of mental health, through absenteeism and presenteeism.

Absenteeism: When there is a loss of productivity related to chronic or habitual workplace absence that is unauthorised, unplanned and unannounced, and includes partial absences like lateness, early departures, and extended breaks.

Presenteeism: When there’s a loss of productivity while being at work due to illness. - – poor mental health in the workplace cost the 2010 global economy around:

≈ $1.7 tn ($1,700,000,000,000.00)

- More recent 2020 data from the US estimated that the total cost of

major depressive disorder alone to be around:

≈ $210 Billion ($210,000,000,000.00) - – this 2020 figure had increased 153% since 2000, with half of these costs being indirect and borne by the employer (McKinsey, 2020)

- In Europe, 2012 OECD data put the cost of poor workplace mental health at:

3-4% of GDP

≈ $439 bn ($439,245,300,000.00) to $586 bn ($585,660,400,000.00)

The co-morbidity of mental and physical health conditions represents an important driver of overall costs and a considerable burden to healthcare systems.

For instance, depression often co-occurs with conditions like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, with 60% of its direct treatment costs attributed to co-morbidities (Hersen et al. 2022). This is linked to the effect that psychological stress has in down-regulating cellular immune response.

Global management consultancy McKinsey (2020) used a large longitudinal Optum prescription data set to explore the effects of depression. It found that obtaining an antidepressant prescription increased the odds of subsequently receiving one for diabetes by 30%, cancer by 50%, and heart disease by almost 60% (McKinsey, 2020).

These findings clearly underscore the tangible benefits for employers – and wider society – in ensuring that workplaces provide practical solutions to improve and protect mental health and wellbeing amongst their workforce.

6. Supporting Mental Health In The Workplace

So what should businesses do to create an environment where employees’ mental health enables them to thrive?

How should organisations go about enhancing productivity and engagement through positive workforce wellbeing?

In their systematic review of research on mental health in the workplace, Wu et al. (2021) argue that the most effective interventions in the field combine primary prevention (i.e. affecting incidence/nature of job stressors directly) with secondary intervention (increasing employees’ ability to cope with stressors). The study also highlights that while existing literature indicates what to do, the more challenging question in application to policy and practice is how to do it, since solutions almost always need to be context specific.

While the importance of the characteristics of each workplace, each role, and each function in determining optimal solutions is clear, the literature on mental health in the workplace, and mental health experts, consistently point at some key factors behind success.

6.1. The Role Of Company Culture In Supporting Mental Health

A company’s workplace culture – defined as a set of deeply embedded norms, behaviours, and dynamics which influence the physical and social environment of the workplace, its values, and the set of unconscious assumptions characterising it – is often overlooked as a determinant of mental health (Hersen et al. (2002), when in fact, it is key.

A robust organisational culture concerning mental health encompasses various facets, from leadership and management behaviour, and official policy guidance documents, to less tangible but equally defining factors such as common practices and expectations, as well as the values of the organisation (Wu et al., 2021).

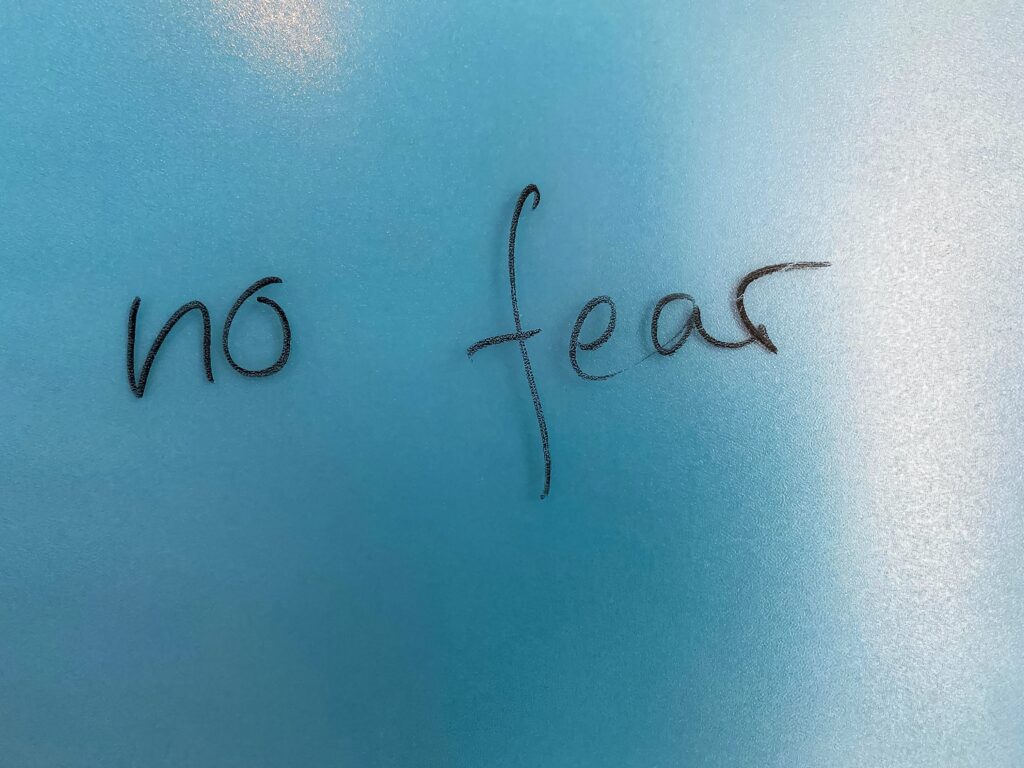

Central to culture’s impact on mental health are embedded company attitudes towards mental health issues, including stigma and norms around disclosure.

Research indicates that the fear of stigma, driven by employees’ concern that they may jeopardise their careers through disclosure, stands as the primary deterrent to accessing mental health support at work (Edington et al., 2016 .

For instance, a study involving over 6,000 employees across 13 workplaces in the USA, found that although 62% knew how to access company resources for depression care, yet only 29% indicated they would feel comfortable discussing the issue with their supervisor (Charbonneau et al., 2005).

A company culture which successfully embeds mental health in all its aspects therefore actively addresses and mitigates the fear of stigma.

6.2 Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) In The Workplace

A high level of mental health literacy within the workplace is an important aspect of fostering a company culture that supports optimal mental health outcomes.

In this regard , ‘Mental Health First Aid’ stands out as a program successfully implemented in a number of OECD countries, aimed at enhancing knowledge and skills on how to recognise common mental health disorders and provide initial aid and support until professional help can be accessed, thereby contributing to reducing stigma (Wu et al., 2021).

Various studies point at the effectiveness of mental health first aid, including two randomised-controlled trials conducted in workplace settings (Kitchener et al., 2004, and Jorm et al., 2010).

The concept of mental health in the workplace is undergoing a significant transformation and moving away from outdated approaches, with many now adopting and benefitting from programs like Mental Health First Aiders (MHFAiders).

MHFAider programs are a win-win for companies and for employees:

- Improved employee well-being: MHFAiders make mental health support more accessible and visible, allowing for early intervention before problems escalate and snowball.

- Reduced absenteeism and increased productivity: Early intervention leads to fewer and shorter absences, helps employees stay at work, and enbales better levels of productivity and less operational disruption.

- Enhanced morale and staff retention: A supportive work environment with mental health awareness fosters a positive company culture and reduces employee turnover.

- Stronger financial performance: By protecting employee wellbeing, organisations ultimately protect their financial health; companies benefit from higher productivity, while reduced talent losses reduces recruitment costs.

6.3 The Role Of Leaders: Opening Up The Mental Health Conversation

Leaders play a key role in defining, shaping, and embedding company culture. In our White Paper about the cost of toxic culture we explore their importance of setting the tone for attitudes and behaviours which are accepted and practised within their teams, and how they play a huge part in embodying (or not) a certain culture on the ground.

A study by Sull & Sull (2022), synthesising existing research on specific elements of corporate culture, found that strong leadership has one of the highest correlations with a healthy corporate culture across all elements. It is followed closely by social norms, which reflect the extent to which corporate values are translated into tangible behaviours.

Leaders are fundamental when it comes to both the implementation of policies that impact on mental health, such as anti-bullying and anti-harassment policies. Moreover, they serve as champions for mental health within their teams and the wider business (Wu et al., 2021). By modelling healthy behaviours, talking openly about mental health, and making its safeguarding an integral part of their role, they become instrumental in changing employees’ perception of the business, while destigmatising mental health. Leaders can also help bridge the gap between employees’ mental health needs and the resources available at company level, by proactively seeking to understand those needs and adapting their management style accordingly.

- Further Reading On Leadership:

📖 Change Management vs Change Leadership

📖 Emotional Intelligence In Leadership

📖 Effective Communication for Successful Leadership

- One-day Workshop: Handling Conflict, Feedback & Difficult Conversations:

A workshop that helps you and your team to foster a positive and collaborative culture, to handle conflict, feedback, and difficult conversations, and navigate through uncertainty.

🎓 Successfully Navigating Uncertainty Workshop

7. Conclusions

The imperative to address mental health in the workplace is underscored by its significant costs to individuals, businesses, and society at large. Data on the prevalence and costs of mental health conditions suggests that the toll of untreated mental health issues extends beyond individuals to encompass diminished productivity, and heightened healthcare expenses, highlighting the urgency and importance of proactive intervention.

Central to fostering a mentally healthy workplace is the role of company culture, which goes beyond mere policy compliance to create an environment where employees can thrive rather than merely survive. As outlined by the WHO definition of mental health, a supportive culture promotes holistic wellbeing by nurturing personal growth, fostering resilience, and encouraging open dialogue about mental health issues.

Leaders play a pivotal role in shaping this culture, serving as role models and setting the tone for discussions surrounding mental health. Through leading by example and actively reducing stigma, leaders can create a psychologically safe environment where employees feel empowered to seek support and prioritise their mental wellbeing.

Furthermore, businesses must recognise the shifting values and priorities of Millennials and Gen Z young professionals, who increasingly prioritise mental health and wellbeing. Leveraging this trend when training future leaders will not only align organisational values with those of the workforce, but also drive positive cultural change and enhance overall employee satisfaction and engagement.

In essence, addressing mental health in the workplace requires a multifaceted approach that encompasses cultural transformation, leadership commitment, and alignment with evolving workforce values. By prioritising mental health and wellbeing, businesses can mitigate the costs associated with untreated mental health issues while also fostering a healthier, more resilient and thriving workforce.

- Beeline Podcast: High Performance Mindsets and a Culture of Wellbeing:

An episode that builds covers the beeline to achieving high performance mindsets whilst maintaining a healthy, happy working culture. (Podcast audio plus episode notes.)

🎧 S2E1: Chris Hatfield: High Performance Mindsets & a Culture of Wellbeing

- Six-month Program: Develop Leadership, Management, and Team Culture:

A program that builds a unified and joined-up team culture, with a shared sense of purpose and direction, improved retention, reduced burnout, and higher productivity.

🎓 Team Purpose Program

References:

American Psychological Association, 2017, Stress in America: The State of Our Nation

Attridge, M., 2019, A Global Perspective on Promoting Workplace Mental Health and the Role of Employee Assistance Programs. American Journal of Health Promotion, 2019;33(4):622-629. doi:10.1177/0890117119838101c

Charbonneau A., Bruning W., Titus-Howard T., Ellerbeck E., Whittle J., Hall S., Campbell J, Lewis SC, Munro S, 2005, The community initiative on depression: report from a multiphase work site depression intervention, J Occup & Environ Medicine, 2005, 47 (1): 60-67

Deloitte, 2022, Striving for balance, advocating for change. The Deloitte Global 2022 Gen Z and Millenial Survey

Edington, D.W., Pitts J.S., 2016, Shared Values, Shared Results: Positive Organizational Health as a Win-Win Philosophy. Ann Arbor, MI: Edington Associates

Euronews, 03/01/2024, The Mental Health of People in Europe is worsening. People in this country suffer the most, accessed on 19/04/2024

Goh, J., Pfeffer, J., Zenios, S., 2016 “The Relationship Between Workplace Stressors and Mortality and Health Costs in the United States” Management Science Vol. 62 Issue 2 Pages 608-628

Hersen, M., Thomas, J.C., 2002,Handbook of Mental Health in the Workplace, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publ; 2002.

Jorm A.F., Kitchener B.A., Sawyer M.G., Scales H, Cvetkovski S, 2010, Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: a cluster randomized trial, BMC Psychiatry. 2010, 10: 51-10.1186/1471-244X-10-51.

Karasek R.A., Theorell T., Schwartz J.E., Schnall P.L., Pieper C.F., Michela J.L., 1988, Job characteristics in relation to the prevalence of myocardial infarction in the US Health Examination Survey (HES) and the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES). Am J Public Health. 1988, 78 (8): 910-918. 10.2105/AJPH.78.8.910.

Kitchener, B.A., Jorm, A.F. ,2004, Mental health first aid training in a workplace setting: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN13249129]. BMC Psychiatry. 2004, 4: 23-10.1186/1471-244X-4-23.

LaMontagne, A.D., Martin, A., Page, K.M. et al., 2014,Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach, BMC Psychiatry 14, 131 (2014).

Mary Christie Institute, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the Healthy Minds Network, the National Association of Colleges and Employers, and Morning Consult, 2023, The mental health and well-being of young professionals.

McKinsey, 2020, Mental Health in the Workplace: the coming revolution

Melchior, M., Caspi, A, Milne B.J., Danese, A., Poulton, R., Moffitt, T.E., 2007, Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men, Psychol Med. 2007, 37 (8): 1119-1129. 10.1017/S0033291707000414.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2012, Sick on the job? myths and realities about mental health and work

Sanderson, K., Andrews, G., 2006, Common mental disorders in the workforce: recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Can J Psychiatry. 2006, 51 (2): 63-75.

Sivris, C. K., Leka, S., 2015, Examples of Holistic Good Practices in Promoting and Protecting Mental Health in the Workplace: Current and Future Challenges,

Safety and Health at Work,Volume 6, Issue 4,2015,Pages 295-304,

ISSN 2093-7911

Smith, T. B., Trimble, J.E., 2015, Foundations of Multicultural Psychology, American Psychological Association,September 2015, ISBN: 978-1-4338-2057-1

Sull, C. & Sull, D.2022, How to Fix a Toxic Culture, MIT Sloan Management Review

World Health Organisation, Mental Health Factsheet, World Health Organisation Website, www.who.int, accessed on 19/04/2024

World Health Organization, 2017, Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. White Paper, Geneva, Switzerland.

The British Psychological Society, 31/03/2023, Burnout – a modern epidemic of occupational stress, accessed on 19/04/2024

Trautman, S., Rehm, J., Wittchen, H., 2016, The Economic costs of mental disorders: do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders, EMBO rep (2016) 17: 1245 – 1249